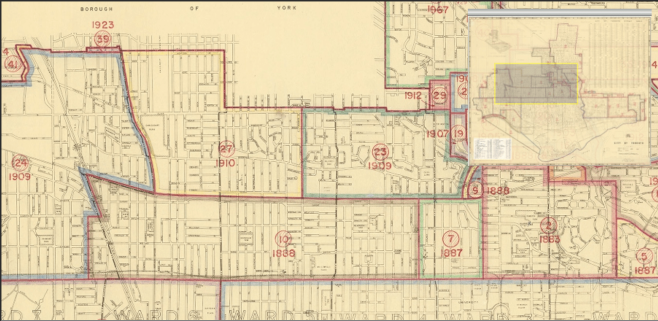

The annexation by the City of Toronto of McRoberts Avenue was for health reasons. According to Nancy Byers and Barbara Myrvold’s award-winning St. Clair West in Pictures (Toronto Public Library, 3rd ed, 2008) concern for sanitation and the spread of disease in other outlying neighbourhoods pushed the city to act. Bracondale, Wychwood, and West Toronto were all annexed in 1909. This made a weird dip in the city map, with Earlscourt stuck between two parts of Toronto. In January 1910, the gap was filled and Earlscourt and Dovercourt became part of the city, officially named “North Dovercourt Annex”.

On McRoberts Avenue, the new city limits cut the street in two. From St. Clair West to just North of Innes Avenue the residents lived in Toronto but beyond that, the street was part of York. As a result, services, infrastructure and taxation rates were quite different. Overall, Byers and Myrvold say, the acquisition of Earlscourt wasn’t that exciting for the City of Toronto. It had a population of only 5,000 people and “it had never been incorporated, and had minimal police and fire protection, and only a few street lights, sidewalks, paved streets, and houses with indoor toilets and running water.”

With all the improvements to be made, the fear of rising taxes was a big issue for the residents. The area was well organized and had an active ratepayers group. They had requested annexation, but only “on the condition that the City guarantee a five-year fixed assessment on unimproved properties which remained in the hands of the original owners.” The city government agreed. Byers and Myrvold cite Joseph Thorne’s experience as a resident of McRoberts Avenue after annexation. His taxes were $2.90 in 1910, and went up by 5 cents the year after.

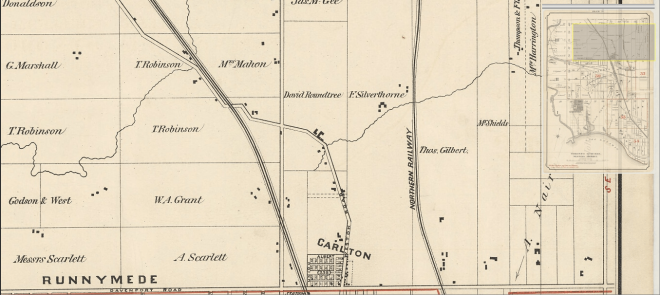

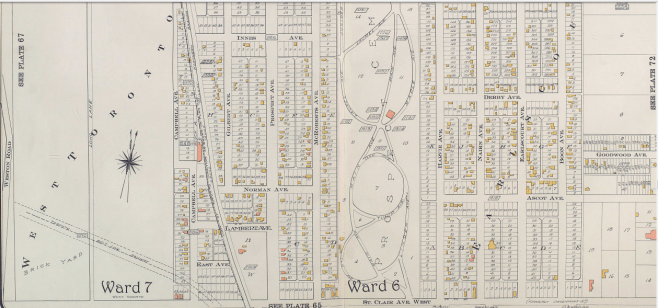

Although Byers and Myrvold say that the area was sparsely populated, the residents of McRoberts Avenue had been making steady progress with their building efforts. Charles Goad’s 1910 Atlas of the City of Toronto shows many buildings – almost all wooden structures (any brick buildings are coloured red) – lining the street in 1910.

Might’s Directory was typically concise and businesslike about the event: “North Dovercourt and Earlscourt which have just been annexed to the City will be found in the suburban part of the directory, as the order of annexation was issued too late to admit of their being included in our city canvass.” The suburban index reads: “Prospect Park (see Earlscourt)”.

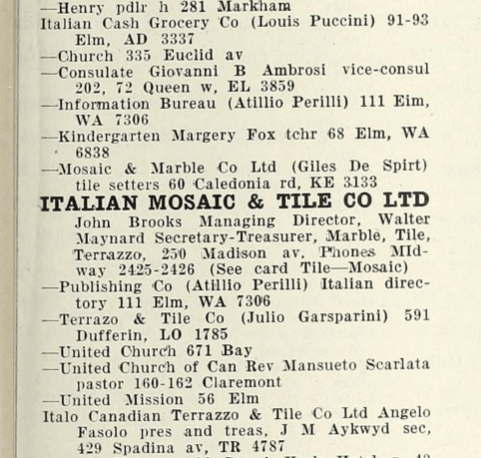

I’ve transcribed all the listings from Might’s Directory that I found on McRoberts that year. By cross referencing with the 1911 Census of Canada, the majority of these households stayed put on the street through the first year of Annexation. Demographically, the neighbourhood was very homogeneous. A typical household was single-family – usually a British-born, married couple in their thirties, with three or more children – who had arrived in Canada in 1905 or 1906. All residents identified a religion, typically Anglican, Methodist or Presbyterian. The main employers for the area were the Canada Foundry (at Lansdowne and Davenport), house builders, the brickyards (in Carlton Village), the CCM Bicycle factory, and the Stockyards. Three people also worked for the cemetery in 1911.

Here is the 1910 residents list from Might’s Directory, showing if they lived on the east side (“e s”) or west side (“w s”) of the street. The letter “l” means they are not the head of the house, but live in that house. Where addresses are given, I am fairly confident that they are referencing lot numbers and not street addresses. Links are added to the names if I’ve mentioned them in another post. Also, most jobs are abbreviated in the directory:

- Blksmth – Blacksmith

- Blrmkr – Boilermaker

- Brklyr – Bricklayer

- Brkmkr – Brickmaker

- Clk – Clerk

- Carp – Carpenter

- Lab – Labourer

- Mach – Machinist

- Mldr – Moulder [a foundry job]

- Messr – Messenger

- Pdlr – Peddlar

- Stone ctr – Stone cutter

- Tmstr – Teamster

Earlscourt (Three and a half miles northwest of PO)

Abbott Wm (Bennet & Abbott), h w s McRobert av

Bates Joseph lab, h e s McRobert av

Beardwood Wilfred lab, h e s McRobert av

Bennett George (Bennett & Wood), h w s McRobert av

Bennett & Abbot (George Bennett, Wm Abbott) coal, w s McRobert av

Buckley John lab, h w s McRobert av

Carpenter John lab, h 22 McRobert av

Cartelage Norman mach, h e s McRobert av

Chapman Sydney foreman Prospect Cemetery, h e s McRobert av

Chown Rev Edwin A Prospect Park Methodist Church res Toronto

Cooper Joseph pdlr, h e s McRobert av

Corish Frederick lab, h e s McRobert av

Dayes John wheelwright, h e s McRobert av

Drury Henry mldr, h 2 McRobert av

Foster Alfred E carp, h w s McRobert av

Foxall George mach, h e s McRobert av

Hains Wm lab, h w s McRobert av

Gray Stephen lab, h e s McRobert av

Haslem Clarence messr, l Frederick Haslem

Haslem Frederick lab, h w s McRobert av

Hayball Herbert driver, h e s McRobert av

Hill Harry dairy, e s McRobert av, h same

Hitchman John tinner, h w s McRobert av

Holden Albert lab, h e s McRobert av

Howey Wm C painter, h e s McRobert av

Huggetts George painter, h w s McRobert av

James Alfred E locksmith, l WA James

James Frederick I tmstr, l WA James

James Wm A bldr, h e s McRobert av

Laird Alfred mach, h e s McRobert av

Matthews Sydney tinner, h e s McRobert av

Maxted Richard lab, h 16 McRobert av

Maxsted Thomas brkmkr, l 10 McRobert av

Maxted Wm brkmkr, h 18 McRobert av

Miller Alfred E mach, h e s McRobert av

Muir John woodwkr, h e s McRobert av

O’Neill James C brklyr, h 24 McRobert av

Osborn Edwin carp, h e s McRobert av

Pigott Philip H lab, h e s McRobert av

Prospect Park Methodist Church Rev Edwin A Chown pastor w s McRobert av

Ripley Thomas mach, h e s McRobert av

Saunders Alfred lab, h e s McRobert av

Savage Charles mach, h e s McRobert av

Savage Sina (wid Henry), h 6 McRobert av

Sier Percy F mach, h e s McRobert av

Smith Wm lab, h e s McRobert av

Stallan Ernest G lab, h w s McRobert av

Stephenson Wm lab, h e s McRobert av

Stone Wm lab, h 11 McRobert av

Thompson James blrmkr, h 23 McRobert av

Thompson Richard, butcher, h w s McRobert av

Thorne Joseph lab, h 17 McRobert av

Troyer Michael lab, h e s McRobert av

Tunner Edward stone ctr, h w s McRobert av

Vanderburgh John carp, h 10 McRobert av

Vanderburgh Raymond shipper, h 12 McRobert av

Vanderburgh Richard, blksmth, l 10 McRobert av

Wall Samuel shipper, h w s McRobert av

Welden Henry lab, h e s McRobert av