This is part 2 of the story of the Del Piero family, covering the years they lived on McRoberts Avenue. Part 1 can be found here.

_____

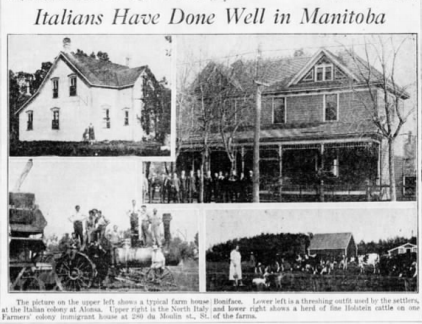

When Giacomo Del Piero left Hamilton, Ontario, for Italy in 1930, he was working as a tile setter. In Hamilton, he was also listed as a “terracer”. This skilled work, creating terrazzo floors, tiling, and creating mosaics, was taken up by many northern Italians. A collection of essays, The Friulian Language: Identity, Migration, Culture (Cambridge University Press, 2014 ed. Rose Mucignat) notes famous examples around the world. Closest to home, this work includes the rotunda ceiling at the Royal Ontario Museum created in 1933, and the Thomas Foster Memorial Temple in Uxbridge. University of Toronto Professor Olga Zorzi Pugliese has catalogued so many of these beautiful installations, from public buildings to private homes, and researched the Canadian companies and some of the craftsmen who created them.

The fact that Giacomo Del Piero went to Hamilton to work must had something to do with his connection to his cousin Aurelio, who ran a steamship ticket agency and shop on James Street North. Aurelio Del Piero was well established in Hamilton. He had been in Canada since 1906 and was one of the founders in the 1920s of the Hamilton branch of the Sons of Italy, a benevolent society still active today.

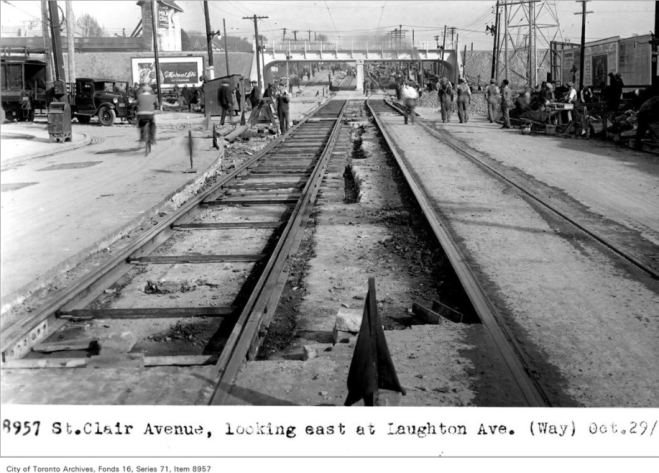

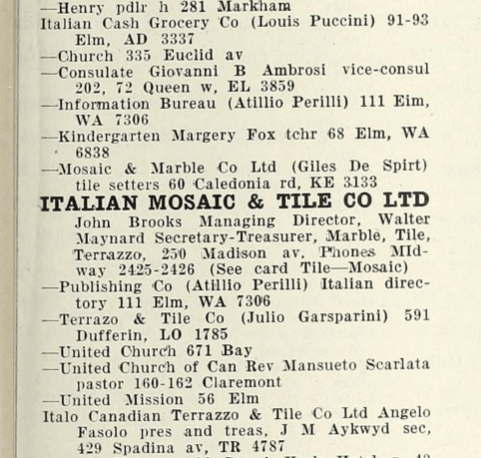

However, when Giacomo came back, alone, from his trip to Italy he didn’t stay in Hamilton. Instead he moved to Toronto, finding a home on Laughton Avenue, south of St. Clair Avenue West. There are a number of Italian households listed in the area west of Caledonia Road in the Might’s Directories of the early 1930s, many of them working in tiling, marble work and terrazzo flooring. Nearby, at 60 Caledonia Road, was the headquarters of one of the city’s leading firms for this type of work: Italian Mosaic and Marble Company of Canada Limited.

A few months after Giacomo’s return, on May 1, 1931, 37-year-old Anna Redivo sailed from Genoa to New York City also aboard the Roma. With her on the passenger list were her three children: Maria Del Piero age 11, Argentino Del Piero age 8 and Alfio Del Piero age 3. The children were all born in Roveredo, but Anna herself was born in Bahia Blanca, Argentina. The Canadian passenger list notes that she is going to join her husband at 125 Laughton Avenue. On May 12, 1931 the family crossed the border into Canada for the first time.

The first few years of the family’s life in Canada were spent on Laughton Avenue. In the 1932 Might’s Directory, Giacomo Del Piero is listed with the first name John, living at 236 Laughton and working as a mechanic at “Italian Mosaic.” This could be one of two companies operating at the time and it is just a guess to know which “Italian Mosaic” employed Giacomo Del Piero, but given the location I’d be willing to bet it was at Egidio DeSpirt’s company on Caledonia.

Research done by Olga Zorzi Pugliese and Angelo Principe for their article, “The Mosaic Workers of the Thomas Foster Memorial in Uxbridge” contains details of DeSpirt’s company, which was responsible for work in many significant buildings such as the mosaic floors in the Toronto Old City Hall, the King Edward Hotel, and the provincial Parliament building.

In 1935, the Del Piero family was listed at 151 McRoberts Avenue, formerly the home of S. Clifford Olmstead, manager of one of the gas stations in the Perfection Service Station chain. In this edition of the directory, Giacomo – now regularly listed as John (just as Egidio DeSpirt went by “Giles”) – is described as a Stone Masher. The next year, he is a stone mason, the trade he will keep for the rest of his time on McRoberts. It is interesting that this period of transition coincides with the contract that Italian Mosaic and Marble Company had won to complete the elaborate marble work in the Thomas Foster Memorial (their competitors, the other “Italian Mosaic”, did the murals).

Another interesting note from this time is that in the federal government’s Annual Report of the Labour Organizations in Canada in 1936, the President-Secretary of the Bricklayers, Masons and Plasterers’ International Union No 16 (Terrazzo Mechanics) was “A. Redivo” at 151 McRoberts Avenue. Later, editions of the Report show “A. Redivo” of the same address in the Secretary role for the Local. Might’s Directory does not list anybody named Redivo in this time period, on McRoberts or elsewhere. It would need more research, but since married women were not usually listed in Might’s Directory unless they were widows, it is possible that Anna Redivo was the labour leader listed in the government directory.

The turbulent politics of the time must have enveloped the Del Piero household. Just considering a few possibilities is anxiety-producing. There were the government’s anti-Communist actions against labour unions, Italian fascist activities in Canada as well as anti-fascist activities by many labour organizations and within the Italian community itself. In addition, there was systemic racism against Italians. Living on a very British street like McRoberts where the local members of the British Imperial Association were regularly reported in the newspapers claiming problems caused by “foreigners” for just about any situation, must have had some dark days.

In Hamilton, Aurelio Del Piero had become involved with the Italian fascist movement and had loaned money for the construction of the Casa D’Italia, which housed fascist organization offices as well as providing space for the Sons of Italy (which was not outlawed as a fascist organization by the Canadian government) and other cultural groups. Research by the Columbus Centre on the arrests of Canadians during World War II includes the imprisonment of Aurelio Del Piero from 1940 to 1941.

In Toronto, the family continued through the war years in their home on McRoberts. In 1938, Maria Del Piero, now 19 years old and known as Mary, had started working for a men’s clothing company at 142 Front Street West called Cook’s Clothing. Warren K. Cook, the owner, was apparently supportive of the labour movement and garment worker’s rights and Mary Del Piero continued to work for his company throughout the war, progressing steadily in her career. Giacomo Del Piero continued to be listed as a Stone Mason.

Argentino and then Alfie came of age just as the Del Piero family decided to leave McRoberts. In 1947, they all moved to Vaughan Road in Fairbank. 1948 is the first year that a new company is listed in Might’s Directory: Del Piero and Son, Contractors. Mary had also risen to the job of Examiner at Cook Clothing. The new residents of 151 McRoberts were another building contractor, Gordon W. Kritzer and his wife, as well as his wife’s sister and her husband, Rev. Charles S. Laidman, a Congregational minister from Binbrook, who had come back to Canada after serving at the historic church in Chicago’s posh Oak Park suburb.