In 1932, Canada was suffering some of the worst effects of the Great Depression. The Canadian Encyclopedia summarizes the impact: “Between 1929 and 1933 the country’s Gross National Expenditure [overall public and private spending] fell by 42%. By 1933, 30% of the labour force was out of work, and one in five Canadians had become dependent upon government relief for survival.” In our neighbourhood, families were increasingly desperate.

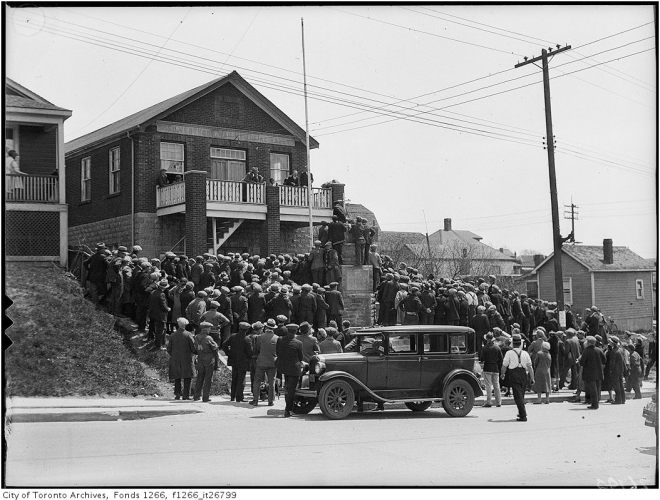

On May 14, 1932, The Globe reported that York Township grocers had appealed to the local police for protection, as did the York Rangers’ Armory in Mount Dennis. They feared violent looting that was threatened by unemployed residents who were rallying in Silverthorn for an increase in the relief money provided by the township. The York Unemployment Association said its members were facing starvation and if help was not forthcoming, there would be no other choice. The Globe reported that negotiations between the York Reeve and the province had averted the impending violence. Relief would be extended by York Township until May 21, when new provincial relief measures would start to take effect.

On McRoberts Avenue, just inside the Toronto city limits, Keith and Louisa Brown of Number 260 could count themselves among the fortunate. Keith was still employed, as a presser at the Fashion Dress Company Ltd. on the third floor of the Tower Building at 112 Spadina Avenue. As a garment factory worker, his employment situation was precarious and potentially volatile. Many workers were subject to intimidation and threats as labour organizers worked to improve wages and factory conditions. A 1931 dressmakers’ strike at factories that neighboured Keith Brown’s workplace included bouts of violence. Some people were assaulted as they walked off the shop floor or as they marched on the picket line.

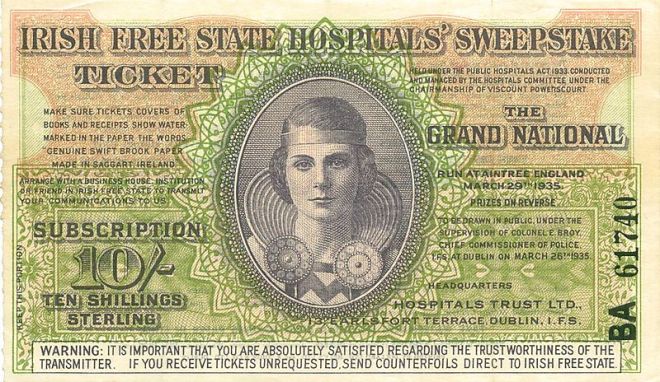

In this uncertain and stressful atmosphere, Louisa Brown joined hundreds of other Torontonians in committing a crime: She purchased a ticket for the Irish Sweep – the Irish Free State Hospitals’ Sweepstakes that promised grand prizes of amazing riches if you were lucky enough to draw a horse that won one of the big races. The May draw for the Derby that year was the biggest one in the Irish Sweep’s short history. Founded privately in 1930 by a trio of Irish businessmen, ostensibly to aid Irish hospitals and health care, the lottery had grown into a global phenomenon by 1932.

Selling and buying the tickets was illegal in Canada – as it was in most places outside Ireland – but it seemed to be possible to hang on to any winnings without major repercussions. A Maclean’s Magazine article published in 1935 describes Canadian winners who collected their money and used it to good, or ill, effect.

The Irish promoters of the Sweeps were famous for their pageantry when it came to drawing the tickets. In 1932, young women were dressed in satin jockey silks and circled their wheeled boxes around the “Golden Hall of Hope” as the tickets were collected and mixed in a large machine (a newsreel film of the strange event can be viewed here). The winners were then drawn by nurses under the supervision of the Chief of Police, to underline the benefits for the Irish state. Historians of the Sweeps, like Marie Coleman, question how much money actually made it to the medical system, but say that at least some good was achieved. Most of the benefit was to the founders, though, as well as to the promoters and overseas agents, many of whom had connections to the Irish Republican Army.

A potential winner would have a ticket drawn and related to a specific horse that would run in the upcoming race. The prize money received would depend on how well the horse did. For the “Record Sweep” of 1932, a Daily Star correspondent stood by, ready to wire the draw results in Dublin back to Canada. The May 31, 1932 Star was able to report that only seven Torontonians (and ten Canadians) had been lucky enough to be among the 644 tickets drawn. A Toronto resident holding the ticket for a horse named Miracle had the best odds of the seven, the Star noted. Most of the local winners were 100-Pound cash prize consolation winners. This would be about $420 Canadian dollars, the Star said.

Among these cash prize winners was Mrs. Keith Brown of 230 McRoberts Avenue. It wasn’t a big prize, but for a family that was probably living on wages of less than $20 a week, it would have provided a cushion at least. It is not known how the Browns decided to use their winnings. Certainly, they did not move right away and Keith Brown continued to work as a presser for the Fashion Dress Company for many more years.

Perhaps they put the money into their house, which they had purchased around 1928. The address was first listed as a vacant property in the Might’s Directory for 1927, so it is likely it was a newly built home and they were the first occupants. The couple had married in 1915 in Toronto, having both been born in the U.K. Keith Brown was from Aberdeen, Scotland, while Louisa Ives was from England. They moved around, renting on Delaware Avenue and Carus Avenue (near Ossington) before buying their house on McRoberts. In the 1921 Census, they had two small daughters, Margarete (age 5) and Kathleen (age 3), although I could not find any further records about the children.

The top Toronto winner of the 1932 “Record Sweep” was Allan Perks, when his horse Miracle came in third, netting him $42,000. Maclean’s tracked him down 1935 and reported that the young office clerk had always dreamed of having his own chicken farm. He had used his winnings to take a course and buy a modern poultry farm in Pickering, Ontario, where he was happily living on 100 acres after having provided for both his parents’ retirement and his younger siblings’ education.

As for the Browns, they remained on McRoberts until 1940, when they moved to Dowling Avenue in Parkdale. From there, Keith Brown would at least have had a shorter commute to the factory on Spadina, where he continued to work as a presser until the end of his working days.