Spring came early to Earlscourt in 1914. In the March 5 edition, the Daily Star reported that blackbirds had been spotted several times, “the harbingers of an early spring.” For the Sherbut and Hay families of McRoberts Avenue, spring also meant that the family trips they had planned back to England were fast approaching. The same edition of the Star, under the headline “To-day’s Best News Items from the Suburbs of Toronto,” said that “Mr. and Mrs. Sherbut and family and Mrs. Hay and daughter, all of McRoberts Ave., will sail on the Royal Edward to Bristol.”

The Royal Edward was one of two steamships owned by the Canadian Northern Railway. It had purchased the ships from a bankrupt Egyptian mail ship company, renamed them the Royal Edward and the Royal George, and had completely refit them by 1911 for trans-Atlantic travel. Their promotional material boasts of many up-to-the minute amenities, including the elegant décor, recreation facilities, and even an electric elevator to carry passengers between decks. In 1914, the company also held the speed record for travel between Canada and England – five days, one way. The Sherbut and Hay (spelled Hey in later records) families were travelling in style.

The two families were next-door neighbours on McRoberts. Clifford Hey, a machinist, lived at 123 McRoberts Avenue, according to the 1914 Might’s Directory. James J. Sherbut, who was a foreman at Swift Canadian Company in the Stockyards, owned the next house up — at 127 McRoberts. Both were wood-frame houses and at that time there were no buildings between them. I imagine Emma Sherbut and Ruth Hey, who were both young mothers, taking a break from their endless daily chores to meet up and talk about plans for their upcoming trip. In 1914, Ruth had only been in Canada for four years but Emma was a few years older and a bit more of a veteran, having arrived in 1906. They had been neighbours for about two years.

Ruth Naylor and Clifford Hey had married in Toronto on May 11, 1911. They were both 25 and living at 110 Greenlaw Avenue at the time, which was close to Clifford’s job at the foundry on Lansdowne Avenue. Before coming to McRoberts, they had moved to 1362 St. Clair Avenue West, near Harvie, where their son Kingsley was born in 1912.

Emma and James Sherbut emigrated together from Devon aboard the Empress of Britain, sailing third class from Liverpool to Quebec October 5, 1906. They had their three-year-old, James John Jr. and infant Fred with them. Little Fred did not survive for very long in Canada; he died on July 23, 1907 and his parents laid him to rest in a child’s grave at Mount Pleasant Cemetery.

The Sherbuts first appear at 127 McRoberts Avenue in the 1911 Census (misspelled as the “Shubuts”). I could not find them in the 1910 Might’s Directory. In the Census, James was 42 and working as a “hidesman,” while Emma was 32 and at home. James Jr. was 8, and they had a toddler named Elsie, who was 2. In the 1913 Might’s Directory, James was described as a butcher, but by 1914 he had been promoted to foreman at the Swift Canadian Company. (There is an amazing photo of the Swift Canadian Company taken in the 1940s here.) Perhaps it was this new boost in income and status that gave the Sherbuts the opportunity to take a family vacation back home. Certainly, James would have needed to take a chunk of time off work to make the voyage.

The Star article says that Ruth Hey was going to travel with her daughter. I have not been able to figure that out. Either the reporter made a mistake and meant her son Kingsley, or she had another baby who I have not been able to find. In the 1921 Census, Clifford and Ruth Hey had two children living with them: Kingsley, and a five-year-old daughter named Almond. I think she would have wanted her family in England to meet her Canadian born son, though.

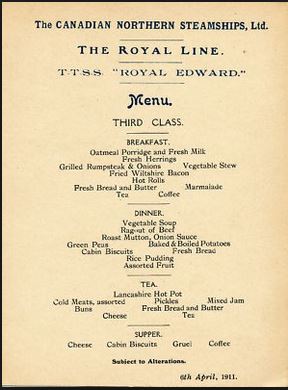

To travel on the Royal Edward, they would have purchased tickets at the Canadian Northern Railway Offices King Street, across from the King Edward Hotel. Having all travelled by ship before, they may have especially appreciated the steamship line’s promotion of an improved standard for second and third class travel. The Royal Edward’s literature spoke of better ventilation and even a roofed promenade deck for the second-class passengers. The menus on board provided solid English fare at breakfast, dinner, and tea with a light supper served in the evening. If Ruth and Emma and their families weren’t suffering from illness on board it must have felt so luxurious to get a break from cooking and cleaning for the better part of a week.

The first leg of the journey was by train to New Brunswick, where the ship embarked from Saint John, sailing out through the Bay of Fundy and on across the Atlantic to Bristol. At that time of year, icebergs were both a sight to behold at sea, and a danger. On a return trip from England that May, the Royal Edward grazed one in a fog, damaging her hull, although fortunately not with the disastrous consequences of the Titanic.

They Heys and the Sherbuts were among the last commercial passengers to sail on the Royal Edward. When war was declared a few months later, in August 1914, the ship was one of many merchant ships to be commandeered for service, her civilian crew adapting and transforming their shipboard routines to provide passage for troops. They travelled in large convoys, always wary of German U-Boats hiding beneath the cold, grey waters of the Atlantic. Just a year later, the Royal Edward was lost, torpedoed in the Mediterranean. The loss of life was heavy. Almost one thousand men died as the ship was at maximum capacity with soldiers being sent to reinforce the British army at Gallipoli. A moving tribute site vividly describes her last voyage.

Clifford Hey and James Sherbut both spent the war years here in Toronto, most likely because their jobs were critical to wartime production. By 1915, the Heys had moved around the corner to 20 Norman Avenue, and another British machinist (at Alsop Process Company of Canada) named George Foxall had moved in at 123 McRoberts. James and Ruth Sherbut remained at 127 McRoberts until 1921, when they bought a brand new, brick home. For the rest of their lives, they would live at 13 McRoberts Avenue, the house that I believe was constructed by their neighbour Walter Griffin of the Griffin Contracting Co. The new owners of the woodframe house at Number 127 were the Worsley family, who would settle there for several years.