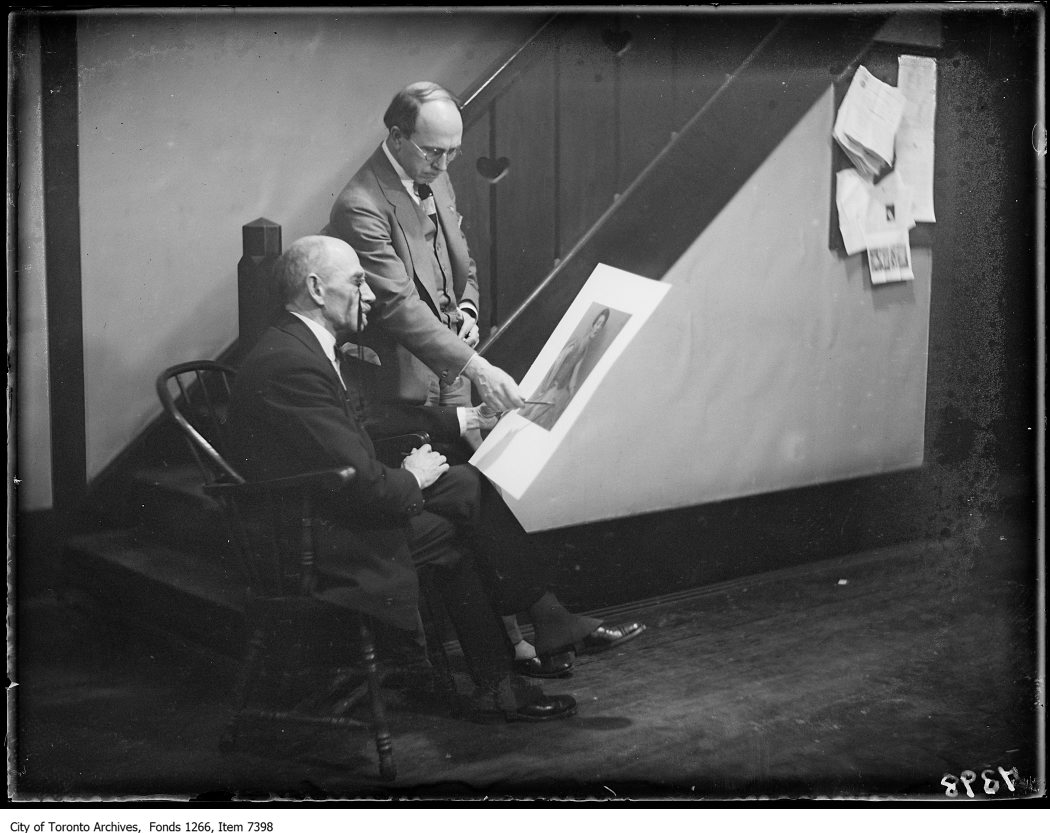

I am grateful to Pam Coburn, author of Hitch, Hockey’s Unsung Hero: The Story of Boston Bruin Lionel Hitchman, and great-granddaughter of John and Amelia Hitchman, for permission to quote passages from her wonderful book. She also generously shared the family photograph of John, Edith and Fanny Hitchman, taken while they lived on McRoberts Avenue. For more on Hitch, Hockey’s Unsung Hero, click here for Pam Coburn’s Web site.

With the NHL playing an all-Canadian division this season, for the first time in almost 100 years, it seems like a good time to write about McRoberts Avenue’s connection to one of hockey’s legends, Lionel Hitchman.

Coincidentally, Canadian hockey lost Hitchman when the NHL first expanded to the United States, adding the Boston Bruins for the 1924-25 season. Ottawa took the opportunity to trade Hitchman to the Bruins for cash, a short-sighted move Ottawa would have reason to regret.

But first, back to Toronto. On September 20, 1888, a 41-year old labourer named John Hitchman arrived in Canada from England on the Allan Line steamship, SS Parisian. Pam Coburn, his descendant and biographer of Lionel Hitchman, believes their passage was assisted as the family struggled economically in the London slums, and John was frequently unemployed due to the desperate economic conditions in England at the time. Coburn believes he was accompanied by his 43 year-old wife Amelia Rachel (Cahill) Hitchman and their three children, although only John is listed on the ship manifest.

The 1891 Census of Canada shows that the family settled in St. Stephen’s Ward. They lived at 162 Dundas (before the street was reconfigured into its current state), near St. Barnabas Anglican Church, where John Hitchman served as sexton (caretaker) of the church. John was 43 and listed as a general labourer. Amelia, age 46, was at home, although Coburn notes that Amelia was working as a nurse soon after arriving in Toronto. Their three children were living with them: Edward Frederick (commonly known as E.F. or Fred) was the eldest. He was 17 and already working as a barber. William was 13, and Caroline, known as Carrie, was 10.

Amelia’s time in Canada was sadly very short. On September 21, 1892, she died of peritonitis. That same day, her doctor, Dr. O’Reilly, reported two other deaths of either enteric fever or peritonitis, suggesting that there may have been an outbreak of typhoid in the neighbourhood. In his typhoid article for a Now Magazine series on Toronto’s past pandemics, Richard Longley’s description of Toronto’s lack of sanitation at this time is truly revolting. Whatever the cause of Amelia’s peritonitis, the family was left in mourning.

The following year, though, John Hitchman married again. Twenty-five-year-old Edith Death, who would likely have known John Hitchman from St. Barnabas, married him on December 28, 1893. John Hitchman had become a tinsmith by this time. According to the Census of England, John Hitchman’s father was a brazier in Stratford, which was a trade involved in making and repairing brass, so John may have learned some metal working skills from him as a boy. According to Coburn in Hitch, Hockey’s Unsung Hero, John Hitchman also worked as a gas stove maker for a time, and as an insurance agent for Metropolitan Life. He was an avid cricket player and musician, and was involved in the Sons of England Benevolent Society for over fifty years. Edith and John’s only child together, Elizabeth Fanny Hitchman, was born at 162 Dundas Street on September 1, 1895.

Young E.F. Hitchman followed in his father’s footsteps as a cricketer, and church and community organizer. He opened his own barber shop at 156 Dundas Street and in 1895 travelled to Clinton, Iowa to marry his Toronto sweetheart, Ida May Thurresson, whose family had moved to the U.S. The couple returned to Toronto and moved in with the rest of the Hitchman family on Dundas. The family stayed on Dundas for several years and had three children, Mary Florence in 1897, Frederick Lionel in 1901, and Ida Dorothy in 1909.

Meanwhile, the rest of the Hitchmans moved house. It seems likely that the family moved to 60 McRoberts Avenue from Dufferin Street sometime after 1904. It was once the city’s practice to ask taxpayers to vote on individual budget items, and a 1904 notice of a referendum published in The Globe on October 21 contains a section for Ward 6, Division 5 voters: “All between the centre line of Dundas Street and the centre line of Bloor Street. Polling place at John Hitchman’s house 781 Dufferin Street.” John and Edith Hitchman were definitely among the earliest homeowners on McRoberts Avenue (click here for a list of all McRoberts residents named in the 1910 Might’s Directory).

Lower property and business taxes could have been among the incentives for the Hitchman family to move outside the city limits, to the fledgling community of suburban homesteaders on McRoberts Avenue. A local tinsmith to repair bathtubs, water buckets, and kitchenware would have easily found customers among the neighbours there. However, without running water and other services, and with a recession following the Panic of 1907, the population was slow to grow. Fortunately, John Hitchman was able to get a job at Prospect Cemetery, where several other McRoberts Avenue residents were also employed. Fanny would most likely have gone to school at the small schoolhouse that was built on Innes Avenue and later replaced by Hughes School.

Back on Dundas Street, E.F. Hitchman was a popular leader with a passion for sports, especially cricket. His younger brother William may have played junior hockey for the Marlboros in 1903. E.F. was often mentioned in the newspapers organizing teams and leagues in the west end. He was also a business leader. On Thursday, June 27, 1901, the Daily Star noted that E.F. was among the main organizers for “the first annual picnic and games of the Dundas street merchants,” which the newspaper said was a new idea. The article continued, “And that explains why last night Dundas Street, from Queen to Arthur, was, by the magic of flags, Chinese lanterns, a blaze of light, the sounds of music and many voices, transformed into a sort of clean Midway Plaisance.”

Ida and E.F. Hitchman were also both active at St. Anne’s Anglican Church in old Brockton. He became president of the Men’s Association at the church, and Ida was made a life member of the women’s auxiliary. They both sang in the choir. The couple would have been heavily involved at the church at the time William Ford Howland designed the current Byzantine style building, although they had already moved to Ottawa by the time Group of Seven painters decorated the church’s stunning interior. In 1913, E.F. Hitchman chaired a meeting of all the protestant Men’s Association presidents in Toronto to create a larger organization, with organized sports leagues being a key motivator.

Like his father, E.F. Hitchman was an avid cricketer, playing for several different clubs during his years in Toronto. As a child, Ida and E.F. Hitchman’s son, Lionel also naturally started to play cricket as well as other sports, including hockey. Pam Coburn writes in Hitch: “While with Grace Church [cricket team], E.F. played with a man who became instrumental in his son’s athletic development, William “Bill” Marsden, a fellow Englishman and noted cricket and rugby player. Bill managed the famed Aura Lee junior hockey team, coaching Hitch and other renowned hockey players, including Lionel Conacher, voted Canada’s top athlete of the first half of the 20th Century.”

Lionel Hitchman’s hockey years really kicked in during World War I, when he played for the Wychwood team, after his mother moved the family to Wychwood Avenue where she could be closer to her mother as well as her in-laws on McRoberts while her husband was serving overseas. Lionel and Dorothy were often cared for by their grandparents, as both Ida and her eldest daughter Mary were serving the war effort by working in a munitions factory. “Hitch and Dorothy were fortunate to have side-stepped most of the ill effects of the war,” writes Cosburn, “and enjoyed a carefree childhood full of literature, music, and sports. Dorothy’s daughter, Tammy McLaughlin, remarked that her mother ‘idolized her brother and wanted to be as good at hockey as he was.’’’

E.F. Hitchman, along with many other cricketers, had enlisted early in the war. He joined the University of Toronto Canadian Army Medical Corps as a private and served overseas in England and Greece. Based at the 4th Canadian General Hospital in Basingstoke, England, Private Hitchman was promoted four times by 1916, becoming Staff Quarter Master Sergeant by the time of his discharge at the end of the war. (There is a souvenir photo album of the hospital on the Toronto Public Library Site, including a photo of the stores that E.F. would have worked in.)

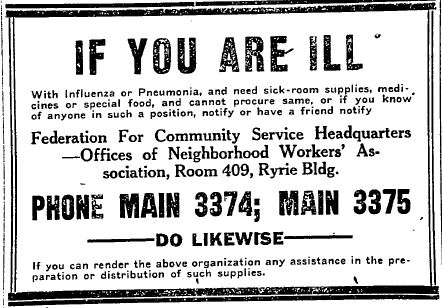

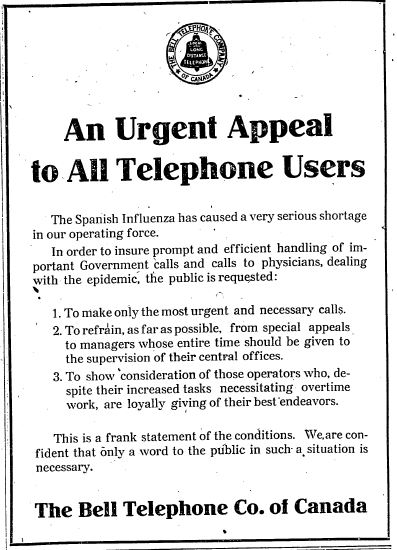

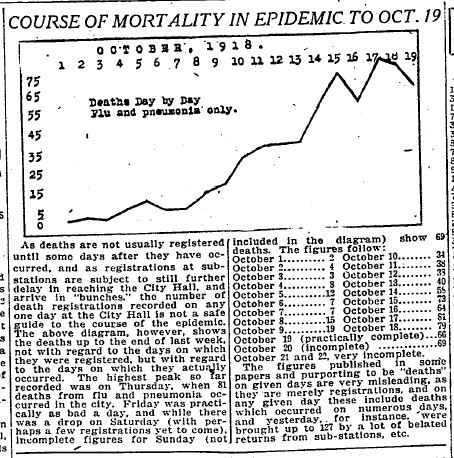

During the war, Lionel Hitchman started high school at Oakwood Collegiate, where he played rugby, helping to win city championships in 1917 and 1919. Pam Cosburn notes they probably would have won in 1918 too, if sports had not all been cancelled due to the first wave of the influenza pandemic in Toronto.

The winter of 1919-1920 was a pivotal one for the Hitchmans for other reasons. First, E.F. Hitchman returned from war in November 1919, and then Lionel Hitchman made the legendary Aura Lee Hockey team, hitting the ice with them in January 1920, just as he started his final months of high school.

Edith and John Hitchman had hosted the marriage of their daughter Fanny to Charles Tubb on October 18, 1919. Tubb was the son of John and Edith Hitchman’s best man, George Tubb, and the couple moved to Bridgeburg, Ontario. Within a year, Edith passed away, dying at Toronto Western Hospital on July 6, 1920.

Living alone on McRoberts was not what John Hitchman wanted. He sold the house and moved to 1397 Lansdowne Avenue, boarding at the home of Cecil Gilbreath, a shoe salesman. There, John Hitchman continued to work as a bookkeeper at the cemetery office and also had a front row seat for the construction of the new Earlscourt Park built in 1920 on the Royce Estate south of the cemetery. Among the park’s first amenities were cricket and soccer fields and a quoits (horseshoe) pitch, all sports the Hitchmans enjoyed. (Click here for the Earlscourt Park 100th Anniversary Web site).

The next residents of 60 McRoberts were the Lee family, who came from England in 1911. William Lee was listed in the 1921 Census as a teamster living with with Minnie and their three young children, who were all born in Canada: Ivy, Doris and baby William. The house is described in the census as a 6-room detached wooden house, so the brick semi-detached homes that stand at the address today replaced the Hitchman and Lee’s original home.

It was also in 1921 that Ida and E.F. Hitchman moved to Ottawa, after E.F. was recruited to work for the Federal government in the continuing effort to resettle returned servicemen. Lionel and Dorothy both moved with their parents. Lionel served briefly with the RCMP, where he played on the cricket team, before launching his famed career in the NHL, which he kicked off with a Stanley Cup for Ottawa. This was followed by his glory years in Boston. His #3 Bruins jersey was the second sweater ever retired by the league.

E.F. Hitchman also developed a wildly successful new career in Ottawa, as a cricket columnist, organizer, and leading Canadian authority on the sport. Like Lionel, he returned to Toronto from time to time for sports business, and his arrival was always celebrated by the press. He wrote for the Ottawa Citizen well past retirement age and has been inducted into multiple sports halls of fame. He was also noted by the Citizen as the second eldest member of the Christ Church Cathedral choir in 1960, at the age of 86.

John Hitchman also had a long life, eventually retiring from the cemetery and making his home with his daughter Carrie’s family on Corbett Avenue, in the Syme district near Jane and Dundas, until his death at the age of 94 in 1941. His funeral was held at the now-closed Anglican Church of the Advent on Pritchard Avenue. He is buried with Edith at a lovely shady spot in Prospect Cemetery, within sight of McRoberts Avenue. Their shared monument is engraved, “In His Keeping.”